That Really Happened

By Ashlee Gadd

@ashleegadd

“The things that haunt us can be left behind in what we make, held safe where they won't continue to torture us. Maybe that is what drives us to make art …

Maybe for some of us, that is how we survive.”

- Cindy House, Mother Noise

It’s Tuesday afternoon and I’m sprawled on the couch with my feet up, laptop perched on my thighs. I look back over my shoulder to steal a glance at the kids through the windows. They’re jumping on the trampoline, playing some kind of bizarre game that involves a great deal of shrieking and throwing stuffed animals in the air. I smile, offering up a silent thanks for all of it: the sound of their laughter, the California sunshine, the beat-up trampoline we bought seven years ago that continues to bless me with uninterrupted minutes.

Despite the occupied children, and despite the sunshine pouring through the windows casting a glow all around me—seemingly hinting at some kind of divine inspiration—writing is not going well today.

I’m doing that thing where I type a sentence and immediately delete it. Type. Delete. Type. Delete. I am trapped in a revolving door, spinning and spinning and spinning, unable to find my way out.

Even so, when my three-year-old daughter, Presley, opens the sliding glass door and tells me she’s just seen a dead mouse, I barely look up from my screen.

“You did?” I ask with a glance, skeptical.

“Yeah, I did,” she confirms. I study her face for a second. Her brows are furrowed and her lips are turned down in a slight frown. She looks like she’s seen a ghost.

“Did you … touch it?” I ask, wondering if I need to wash her hands.

“No,” she shakes her head.

“Okay, well …” my voice trails off as I return my gaze to the laptop screen, “Sorry that happened, babe.”

I do not get off the couch. I do not offer any follow-up questions. I do not ask her to take me by the hand and show me what she’s seen. I make a mental note to tell my husband later, and basically blow the whole thing off.

Presley hovers near me for a minute, while I go back to typing and deleting.

“I know! I’m gonna draw it!” she tells me with wide eyes, running toward the dining room as if she’s just had an epiphany.

“You’re going to draw the dead mouse?” I ask.

“Yep,” she confirms with a nod.

She grabs a fresh piece of white paper and a basket of crayons from the art cart that sits next to the dining room table. Then she climbs up into a chair and gets to work. For the next several minutes she sits there, quiet, focused, hunched over her artwork in progress.

When the boys come inside a few minutes later, I tell them what Presley said and ask if either of them saw a dead mouse in the yard.

Carson shakes his head. “I think she just saw a rock?”

This is where it’s hard to be three, because once my eight-year-old suggests that Presley mistook a rock for a dead mouse, I, too, become convinced she must have seen something else.

The day goes on, and by the time I go to bed, I have all but forgotten about Presley’s claims.

Three years ago, I began writing a book on the bathroom floor.

Crouched on a tiny plastic stool, I scribbled ideas down on multi-colored index cards while Presley splashed water all around me. I still have a bunch of those cards—a weird souvenir of sorts—stashed in a bag in my closet. A lot of them are stained with water spots, the ink blurred and hardly legible. Like the visible handprints on our sliding glass doors, I see those water spots as evidence my children were here, leaving a mark on everything I do and everything I create.

The irony of writing a book about motherhood and creativity during a global pandemic is that the entire message of the book was immediately put to the test.

Creativity enriches motherhood! I claim.

Creativity is worth pursuing! I insist.

Really? Even when the world’s on fire?

While I wrote pieces of this book sitting in my car parked in the driveway, fueled by coffee, silence, and a strong Wi-Fi signal, I had to ask myself over and over again: Is this really true? Do I really believe these words I am writing?

Does the act of creating matter to mothers?

Peel back another layer. Does the act of creating matter at all?

The morning after Presley’s alleged dead mouse sighting is chaotic as usual. The boys need to be at school by 8:45. My husband has a meeting from 8-9:30. I have a meeting at 9, and Presley needs to be at dance class at 9:30. All of us spin around the house like mini tornados—getting dressed, inhaling breakfast, packing bags, and filling up water bottles.

I am about to get in the shower when Brett pulls me aside and whispers, “Hey, there’s a dead possum in the backyard. Don’t let the kids go outside, I don’t want them to touch it.”

I scrunch up my face in horror. Gross.

It is not until I am halfway through my shower, mid-shampoo, that I connect the dots.

A memory flashes through my mind: me, sixteen years old, driving to my high school in the dark, probably for cheer practice or a basketball game, and seeing what appeared to be a giant rat run out in front of my car. I gasped, slammed on my breaks, and said out loud to absolutely no one, “What was that?!”

Later that night, I logged onto my computer and typed “giant rat” into askjeeves.com. After combing through the search results, I discovered what I had seen—and almost run over—was a Virginia opossum (commonly referred to as “possum”). I had never encountered one before.

Once I’m out of the shower, I open the sliding glass door of our bedroom to peek outside. The dead possum is steps away from our bedroom. It’s huge, the size of a cat. The mere sight of its lifeless body makes my stomach churn.

I turn my eyes away, suddenly struck with horror, wondering if that’s what Presley saw.

The day I learned the baby in my belly had no heartbeat, words began filling up inside my head so fast, like lava climbing the walls of a volcano, I knew I had to put them somewhere or I would explode. I came home from the doctor’s office, crawled into bed with a heating pad, and wrote frantically in between choking back sobs.

Some of it came out like poetry. Some of it came out completely unhinged. How it came out isn’t the point, though. The point is: it came out. The lava erupted and found a safe place to land. The blank page.

I was pregnant one minute, and then I wasn’t.

My fragility, my pain, my grief, my distress—every feeling coursed straight through my body and into those words. Like evidence left behind, like my own handprint on the sliding glass door, my words bore witness to a broken heart. That really happened. And this is what it felt like.

Brett and I pick Everett and Carson up from school. They’re out early for parent-teacher conferences and we have roughly thirty minutes to kill before our first meeting with Carson’s teacher. We take the boys out for a quick lunch, where Brett finally tells them what he found in the yard this morning.

“Can I see it?!” Everett asks, desperate to look at the picture my husband had snapped on his phone. Carson’s eyes light up as well. Boys.

“Not while we’re eating,” Brett says.

When we get home, all three of them head to the backyard. Everett and Carson practically sprint with glee. You’d think they were going to see the eighth wonder of the world the way they ran outside to gawk at that dead possum. Presley is at a friend’s house with a babysitter, and I’m relieved she’s not home to witness the disposal.

Back inside, I find the drawing Presley made sitting on the dining room table. I pick it up, looking for clues. The paper contains nothing but a blob colored with a brown pencil, featuring a few scribbles all around it.

I’ve heard that you shouldn’t try to understand abstract art, but rather, let it speak to you. I study my daughter’s creation. What is this haphazard blob saying to me?

Your daughter was upset, and you did nothing.

Your daughter confided in you, and you didn’t believe her.

Your daughter came to you in a time of need, and you couldn’t be bothered to look up from your laptop? Really?

I place the drawing back on the dining room table, overwhelmed with remorse.

When I write about motherhood and creativity, I tend to focus on the bright parts—looking for hope, capturing beauty, going where the light is, etc.

But there’s a whole other side to making art.

Sometimes we make art when our hearts are broken, when the waves of grief come crashing out of nowhere, knocking us off our feet.

Sometimes we create to process our trauma.

To move forward. To forgive. To heal.

Sometimes we create to make sense of the world, make sense of our life, make sense of what we’ve just seen in the yard.

Over dinner, I ask Presley if the dead mouse was big, wanting to know once and for all what she really saw out there.

She shakes her head no.

Realizing my three-year-old might not have a good grasp on what would be considered “big” or “small”—I try to clarify.

“How big was the dead mouse, Pres? Was it this big?” I ask, holding up my hands close together, spaced 3-4 inches apart.

“Or was it this big?” I ask again, reaching my hands wide, 15 inches or so.

She considers the question thoughtfully, and then raises her own little hands in the air.

“It was dis big,” she says, reaching her arms as wide as a cat.

Brett and I lock eyes. Mystery solved.

Before bed, Brett opens up the Ring doorbell app on his phone. We have two cameras in the backyard, and sure enough, he is able to find the exact moment that Presley saw the dead possum.

“Babe, this is gonna break your heart,” he says, handing me the phone.

I take the screen in my hands and watch a short clip of Presley walking toward the dead possum, staring at it for a few seconds, frozen, before turning around and running to the sliding glass door, where she had come inside and immediately told me what she had seen.

My husband was right—my heart breaks watching the footage. And for probably the 400th time in my mothering, I desperately wish for a do-over. I wish the second my daughter had come into the house with tales of a dead animal sighting, I had shut my laptop and said, “Tell me more.” I wish I had gone back outside with her. I wish I had consoled her. I wish I had comforted her, hugged her, said something, said anything.

Even more, though, I wish I had acknowledged that what she experienced was real.

Here’s what I will remember about the day Presley found a dead possum in the yard: my daughter came to me, visibly upset, and I blew her off.

In response, she grabbed a piece of paper and made art.

After seeing something scary, she immediately took the experience to a blank page, documenting what she had seen. Proof for herself, if no one else. Evidence captured in real time with colored pencils: that really happened.

And while I still regret my apathy in that moment, I hope Presley takes that instinct with her for the rest of her life. I want my daughter to know that any time she sees or experiences something unsettling in the world—any time she feels that lava rising up inside the walls of her chest—she can listen to that impulse. The one that tells her to grab a blank piece of paper in response. The one that tells her to make a poem, or a drawing, or a song.

Sometimes we create from an overflow of joy, an abundance of delight. Those moments when we’re bursting with love and wonder and hope, and have no choice but to capture the overwhelming gratitude of a moment, the sheer miracle of being alive in this world, of being a person who has witnessed ladybugs and baby toes and sunsets that take our breath away.

Other times, we create from the darker parts of life, the ashes and underbellies and storms. A dead possum. A silent ultrasound. The trauma of having survived a deadly virus. For this, too, is fertile ground for art—the things we’ve cried over and been changed by.

In both the good and the bad, we create as a response to what we’ve seen, as proof of what we’ve witnessed. There are traces of our humanity left all over this planet in forms of art. We know none of it will last forever. Lava turns into volcanic rock, which eventually turns into soil. Our bodies themselves will eventually turn to dust. And still, we make. We leave our mark.

Handprints on the glass.

A book written during a pandemic.

A picture of a dead possum.

We were here.

We were here.

We were here.

All of it really happened.

Words and photos by Ashlee Gadd.

Ashlee is a wife, mother of three, believer, and the founder of Coffee + Crumbs. When she's not working or vacuuming Cheerios out of the carpet, she loves making friends on the Internet, eating cereal for dinner, and rearranging bookshelves. You can keep up with her work at Substack.

All photos seen here (except the last one) were shot on film during the pandemic.

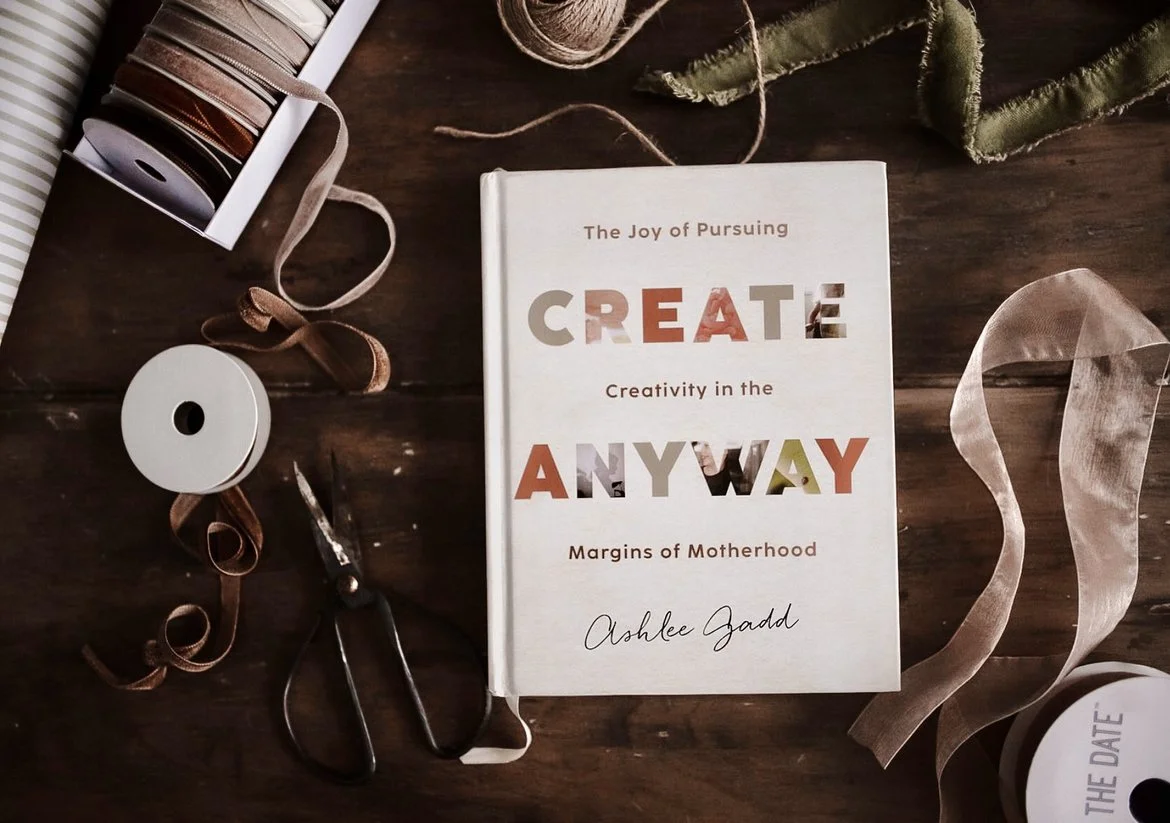

If you enjoyed this essay, you’ll love Ashlee’s new book, Create Anyway: The Joy of Pursuing Creativity in the Margins of Motherhood, hitting bookshelves March 28th.

Preorder now, wherever books are sold.